| Yogananda was an adherent, then a seeker, then a practitioner, then a Kshatriya (teacher of yoga to the west), and in the end of life was a sage. |

| celibacy.info

The Five Stages of Religious Development

COPYRIGHT 2010 JULIAN LEE Adherent -- Seeker -- Practitioner/Devotee -- Kshatriya -- Sage Hindu religion has many levels of understanding and practice. You might say Hinduism is very "catholic." And in Catholic terms you could call their various religion-levels as vocations and rites, or as the difference between practices for the laity and practices for priesthoods and orders. There is something for every level of religious understanding in the Vedanta and the Hindu Upanishads. "Vedanta

means the essence of the Vedas, as described in the Upanishads, the

Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita. It includes three main systems of

Indian philosophical thought, namely, dualism, as taught by

Madhvacharya, qualified non-dualism, as taught by Ramanujacharya, and

absolute non-dualism, whose chief proponents are Gaudapada and

Sankaracharya."

The Upanishads, Volume II, Swami Nikhilananda, p. 205 Even the first of those three categories, dualism, represents a plethora of practices and even sub-religions within Hinduism. The last category, absolute non-dualism, can be said to overarch and encompass all of them. In absolute non-dualism an aspirant has no call to argue or dispute with anybody about religion. He sees all the various outer religions and philosophies -- including their advocates, and thoughts themselves -- as more of the varied phenomena arising in Brahman. "Universes arise in the infinite

consciousness like bubbles on the surface of the ocean."

Yoga-Vasistha, p. 517 None of them are especially "wrong" to the non-dualist. He considers that all manner of things -- and all manner of conceptions -- arise in God, or the "pure consciousness." This extends to systems of metaphysical law, whether theorized or in apparent actual effect. "However the mind conceives

niyati (the natural order) the order becomes."

Yoga-Vasistha The non-dualist views even the very opponent preaching a particular doctrine, and the ideas he argues, as a projection of himself. All things dealing with categories of dualism or the realm of words have no significance to him. This point-of-view is the province of the yogic saint. But for those of us not established in the non-dual awareness (most of us); not cognizant of the manner in which we project the outer world-dream, various forms of religion and religious practice benefit us and lead us onward. God has a practice and philosophy right for everybody at their stage of understanding, and Hindu texts have no shortage of possibilities. The scriptures themselves adduce to levels and stages: "The mind is desire and the

cessation of desire is moksa (liberation): this is the essence of the

scriptures...

If you cannot overcome desire completely, then deal with it step by step." Yoga-Vasistha p. 520 It is possible to formulate from the multi-faceted Vedic scripture a coherent yet extensive vision of religion. Going back as far as the Dharma-Manu Shastra their texts speak of natural stages of life with spiritual ideals prominently featured, representing a progression and increase in spiritual knowledge. The traditional Hindu formulation of sequential life-stages consists of these four stages: Brahmachari stage The time of youth

and study. It corresponds to the

social class called the sudra

or worker/servant.

Grihasta stage The period of the

householder/husband/father and fulfillment of worldly desires. It corresponds to the

social caste called vaisya

or merchant class.

Vanaprasta stage It means forest dweller or

hermit. This is the older male getting serious about

renunciation, most family

responsibilities behind him, with a

growing tendency to hermithood, scriptural study, and meditation

but now with

responsibilities for the weal of his larger community,

society, or king. He works for the protection and uplift of

his society, and of dharma, while

devoting increasing time to solitude, austerities, and meditation. It corresponds to the caste

called the kshatriya or warrior.

Sannyasi stage The final stage

is a full renunciant who detaches from the world completely and

seeks nothing but God, wandering homeless without possessions

or

staying in near total seclusion meditating and practicing austerities. Corresponds to the caste

called brahmin.

It is said that these four stages represent preparation, production, service, and retirement. The Hindu formulation integrates rarefied spiritual ideals -- even hermithood and homelessness! -- with the naturalistic processes of marriage marriage and family. Our 5-stage formulation is a better match to modern reality and suited to the western mind in this time. Again, our formulation for the west is here: Adherent -- Seeker -- Practitioner/Devotee -- Kshatriya -- Sage One difference is a focus on religious and spiritual development alone, unhitched from the natural life states such as youth and marriage. This gives better understanding of religious phases long experienced by westerners such as The Seeker, bringing them into a respectable legitimacy and affirmation, and into the light of understanding. Following are some ways our formulation differs, with rationales: Identifying the the seeker stage and freeing it from youth-only In our formulation a Seeker stage is explicitly identified, recognizing the legitimacy and importance of this phase of religious development. In the Hindu formulation, this seeker phase is presumed to exist within the brahmachari phase, the phase of the youthful student. We dislodge it from its implied place in the period of youth, don't limit it to that age, and acknowledge that the Seeker state can occur at any age, and more than once. Even longtime church members will periodically become restless for deeper confirmation in their faith. A church should understand this and be able to deal with it by bringing their congregants into some deeper knowledge. Seeker phases of mind occur both in longtime church adherents, and those alienated from western religion. Some may wander from their formal congregation in search of profounder religious understanding and spiritual knowledge. This is a critical phase of spiritual and religious development, can happen at any age, and can repeat as the aspirant reaches plateaus of understanding in a process of spiritual evolution. It needed to be named more correctly. It's not the youth, but the seeking. In ancient Indian culture young men would be sent to study religious knowledge under a guru. In Vedic lore the young males in the brahmachari phase come to a sage in an attitude of spiritual seeking, or at least this was the ideal. They should indeed be full of questions or the guru is not much interested in them! So Hinduism's period of youth was considered a natural time of religious seeking. It is indeed true that we are especially restless and searching in youth, and we challenge and test what has been handed to us in the simple Adherent phase of childhood. We want to know the why and the how of things. A young man gets many questions. This is part of the grace and naturalness of the Hindu formulation. But this formulation presumes all young men to be spiritual seekers. In practical life, and certainly in the west now, youth are often not religious seekers. Meanwhile, strong impulses of religious search can arise at any time, including middle age, while parenting, or in old age. And some rare individuals like Ramakrishna and Joan of Arc become driven God-seekers right in childhood. Youth comes and goes for all, with and without religious yearning. Designating the phase of Seeker is more useful than a stage pinned to youth. In the west, with it's religious breakdown, ferment, and confusion it is needful and resonant to cite the condition of " Seeker." Westerners know Seekerhood very well! Consider how there are no aspirants and no real followers without a seeker. And a religious Seeker -- someone with a yearning to know more about God or to get a religion that he can have complete faith in -- is a higher thing than a mere Adherent who is going through the motions of religion and not applying his whole self. God loves a seeker of truth. Note: The Hindu formulation is based on a very ancient Vedic culture, an almost mythic age that was implicitly and explicitly religious. Our modern culture is a far cry from it. Due to the Kali Yuga and mass cultural degeneration, most of the assumptions and social conditions in place then simply do not exist on a mass scale in the west. One reason seekerhood is pinned to youth is the yogic belief that the young man has the most capacity to comprehend religion and divinity, the best capacity to meditate, and to purify himself inwardly. This is directly related to his comparative moral purity; his undebauched virtue, and his basic sexual vitality. The sexual vitality fuels the mind-engine of meditation, and the kundalini-shakti prefers an unadulterated sexual ground and a pure moral nature with that creative energy devoted to God. The kundalini-shakti grabs hold of the male's sexual energy, uses it, and subsumes it. In a sense it is the interface with the kundalini-shakti, but only the chaste, unadulterated, and undisturbed sexual energy. Thus in the yogic lore a man who begins spiritual practices later in life, and especially one who has been a sexual libertine and debauched himself, has a lesser chance to meditate well, get samadhi, engage with the kundalini-shakti, hear Aum, and get enlightenment. So in this way the Hindu formulation, again, has a wise elegance and there is an essential linkage between the state of youth and the state of seeking. It was the young male who had the best prospect for catching hold of transcendental experience, upon which he'd keep hold of it after entering conventional life. However, our western society is a long way from that society. There will be no sudden mass return to that time. A time when every teenage man is well-grounded in religion, has the value of chastity clarified from an early age, accepts religious instruction in his teens under a religious mentor, with a society honeycombed with enlightened sages and their hermitages to whom mother and father might send their son. The new formulation we present is more suited to the current western condition, and lets men and women set foot on the spiritual train from any condition. It elucidates the spiritual stages in a way westerners can relate to at this time and has the capacity to lead them gradually back to the dharmic state. Separating out the chastity ideal (brahmacharya), generalizing it, and acknowledging its value in all phases The Vedic scripture states that the young men in the brahmacharya stage come to the sage "fuel in hand." This refers to their chastity and the ojas-shakti stored up in the body, brain and spirit. This will be required for effective meditation, and for comprehending spiritual knowledge at all -- especially the mind-rocking non-dualism of the Yoga-Vasistha and Mandukya Upanishad. The first Hindu stage is indeed called brahmachari because: 1) continence is essential in order to comprehend spiritual knowledge, and 2) continence is necessary to meditate and penetrate with the mind, and 3) getting moral self-control and becoming continent is the number one challenge for a young man and the critical issue in his future success in both worldly and spiritual realms. However, the chastity principle has importance and significance in all phases of religious search, not just for the youthful seeker. Continence and morality are needed for anybody pursuing religious knowledge or discipline, at any time of life, and should be separated out as an overarching value relevant in all phases, even the family phase. (The more morally self-controlled a man, the more likely he is to marry and father children. The more morally uncontrolled, the less likely to marry, father children, or be a strong father. Moral self-control gives sanctity to the sex act, gives it weight in marriage, and helps the creative energy reach its goal.) The increasing chastity of a husband (a grihasta), after having the children he and his wife desire, will greatly strengthen his spiritual development, plus give him and his family greater prosperity. Chastity benefits all ages and states, not just youth. Thus we have relabeled the Hindu brahmachari phase as the Seeker to acknowledge that real seeking can occur at any particular age, and that a chastity ideal has inestimable value in all religious stages, including the father/householder. (It takes so few lapses in continence to create a big family, and marriage should not become a man's personal brothel.) The "householder" stage in Hinduism (grihasta) is another natural life course develops for some and not others, and comes naturally and according to karma on its own timetable. There is also no hard, non-negotiable link between that natural life development and any particular spiritual stage. Clearly, we often see householders going through the states of Adherent, Seeker, Practitioner-Devotee, and Kshatriya. Meanwhile the five spiritual stages can be experienced by those who have never married or had children. Sometimes it is seen that family/parenthood encumbers and blocks spiritual impulses. Other times we see family life informing and stimulating a man's spiritual feeling. Though fatherhood deepens and broadens a man's humanity, makes him more inclined to serve and protect his community in maturity, and adds to his wisdom and good instincts later as a father figure for society (Kshatriya) -- being a husband and father is not a pre-requisite of spiritual life or the Five Stages. This is adduced by the lives of many saints from Sankara to Sai Baba of Shirdi to Nityananda of Ganeshpuri. Thus both youth and householderhood have linkages removed from any these five spiritual stages of spiritual development. These two principles that should be remembered in this formulation: 1) In the period of youth, once called brahmacharya, there is indeed a special call and dire necessity to help the youth develop moral self-control through clear moral teaching, development of talents and skills, engagement in productive work, and development of meditation ability. The teaching of brahmacharya (moral continence) should indeed be most vivid and compelling during youth. 2) The natural householder period has a definite spiritual significance in that human desires get fulfilled, men and women come to see the limits and disappointments of worldly pleasure, and they come to understand the point-of-view of a father/mother which makes them more reliable and beneficial Kshatriyas later who protect society. It also deepens their comprehension of the personal God, giving understanding of God's father/mother nature as they become devotees, and like children beseeching that father/mother. Another point could be made, and that is that no one's prayers and God-supplications are stronger and more fervent than the prayers of a mother or father for the protection of their children, and few motivations for God-contact are stronger than the motivation of a divine errand for his family. Family concerns add fuel to prayer and force to meditation. Hindu and Christian Scriptures Address All Five Stages Scriptures like the Bhagavad-Gita speak to multiple levels of knowledge and development. The levels they reference include the Adherent, Seeker, Practitioner-Devotee, Kshatriya, and Sage. Likewise the Upanishads. Some Upanishads focus on ritual, rite, and sacrifice which is the domain of the Adherent. Some focus on meditation practice which is the domain of the Practitioner-Devotee. Some verses in the same scriptures advocate the service imperatives of the Kshatriya, who has been strengthened by yogic practice, is beginning to receive illumination, and knows with conviction that his cultural heritage and dharma are a priceless thing to preserve for his people. And some scriptures clearly apply to the mysterious silent Sage established in his strange state of the non-perception of differences in creation. Levels of teaching are similarly apparent in the Christian scriptures, with some teachings that are very easy to digest and apply in everyday life, others more abstruse, and some sayings -- such as Christ's extreme statements about renunciation -- downright difficult for the average person to accept. Christ even made reference to these relative levels of difficulty. For example, in His "eunuchs" statement about celibacy, he ended with the caveat: 'But this is a very difficult teaching and few can even hear it.' (Our paraphrase.) This teaching of celibacy (Matt 19:12) can easily be identified as a teaching not intended for the simple Adherent, but only for the serious Seeker, the better Practitioner-Devotees, the Kshatriya, and the Sage. It is really the special province of the Practitioner-Devotee, who is typically the first of the five who becomes serious enough to consider such difficult renunciation and who first discovers its significance. The original Christian Church reconciled these apparent differences in level by having a priesthood as distinguished from a laity, then orders and grades within the priesthood. The Five Stages in the Bhagavad-Gita The Bhagavad-Gita clearly speaks to multiple levels of religious practice, and it's seemingly multifarious ideas and teachings key quite handily to all our five stages. In the following verse Krsna speaks of the Kshatriya, the man of maturity, most of his household duties over, having been a Practitioner-Devotee and gaining spiritual fruit, with his continued worldly obligation to protect and guide his society: "King

Janaka and others attained perfection verily by action only; even with

a view to the protection of the masses thou shouldst perform action." 3:20

While the Seeker stage is fiery, focused, and passionate the stage of the Kshatriya is a profound, exquisite mix of several stages. Often having been a family man he has the sensibilities of a householder and father, which gives him good instincts about the well-being of his people and community. He is pursuing techniques for God-contact such as meditation, seclusion, and austerities and getting fruit from them. Yet he is still in a state of seeking. Because until final liberation all yogis remain God-seekers and the very practice of meditation is a seeking quest within. The Kshatriya still sees the dualistic world and deals with it as it is, according to duty. But now he begins to study non-dualistic Vedanta, which is the final frontier of religious and scriptural knowledge. Increasingly he will know ananda or bliss as the background of his mind. Occasionally he will practice seeing all others as emanation of himself, which is the stable province, only, of the Sage. He may even have spontaneous experiences of non-duality. He will have spontaneous spiritual love for others, and no matter how he may be fierce or lawgiving to the people, he does it from an instinct of love. The Kshatriya will have occult signs of meditation progress and even samadhi states. In his advanced practice, in order to get more stability of mind he will try to follow the Yoga-Sutras advice to respond with delight in the virtuous, sympathy for the sorrowful, but to ignore the wicked. Yet the Kshatriya has one more set of layers in his life: He has a role and duty in guiding the people and punishing the wicked. The Kshatriya is like a father figure to his people and society. Even Krsna, who's identity he strives to merge with and who is associated with non-duality, takes on such labors: "Whenever

there is decline of righteousness, O Arjuna, and rise of

unrighteousness, then I manifest Myself. For the protection of the

good, for the destruction of the wicked and for the establishment of

righteousness, I am born in every age."

This refers both to the Divine incarnation's activities, while embodied, in rebuking (even destroying) the corrupt. It also refers to God working through his saints, kshatriyas, and deputies. They also rebuke and destroy the wicked by His will whether during His incarnation or at other times. Krsna destroys the wicked both when incarnated, and in other times through his deputies and these are the Kshatriyas, the warriors. The Kshatriya phase is a very complex and wise state, and they have two predilections: Seclusion and spiritual revelation, and activity on behalf of their society and people. In tradition the Kshatriyas -- who care about their people fiercely yet who have cultivated wisdom, justice and detachment -- are desired as the best advisors, administrators, and deputies of kings. In the same chapter of the Bhagavad-Gita the duty-free, impassive Sage, established in non-duality, is referenced: "But

for that man who rejoices only in the Self, who is satisfied with the

Self and who is content in the Self alone, verily there is nothing to

do." (He has no external duties, imperatives, or

obligations.) 3:17

"Who is the same and pleasure and pain, who dwells in the Self, to whom a clod of earth, stone and gold are alike, who is the same to the dear and the unfriendly, who is firm, and to whom censure and praise are as one." 14:24 Note: None of these comments speak to the matter of detachment from works, which is a karma-yoga attitude and technique relevant to all the stages. This Sage is the final fruit of religion, the final fruit of the Bible and Vedas, and the true gem of any culture. Where he lives, and where the people revere him, welcome him and feed him, the culture will be protected for eons. Elsewhere the same Gita speaks of the religious life of the conventional religionist and the young, or the Adherent: "The

righteous who eat the remnants of the sacrifice are freed from all

sins; but those sinful ones who cook food only for their own sake

verily eat sin." 3:13

(Referring to rituals of Hinduism

involving food. These rituals are not necessary to the sage established

in Brahman.)

"With this do ye nourish the gods and may those gods nourish you." 3:11 Here the Gita speaks to the Seeker stage: "Know

That by long prostration, by question and by service; the wise who have

realized the Truth will instruct thee in that knowledge." 4:34

And to encompass every sort of Adherent, religionist and Seeker: "In whatever way men approach Me

even so I reward them; My path do men tread in all ways, O Arjuna."

And in a great many places the Bhagavad-Gita speaks directly to the Practitioner-Devotee and the yogi: "Let the yogi try constantly to

keep the mind steady, remaining in solitude, alone...

"There, having made the mind one-pointed, with the actions of the mind and the senses controlled, let him, seated on the seat, practice yoga for for the purification of the self." "...firm in the vow of a Brahmachari (celibate)...let him sit, having Me as his supreme goal." The borderline between the Practitioner-Devotee and the Sage (who knows non-duality) is ananda, which increases by meditation, and the state of samadhi which involves the higher reaches of ananda. After knowing the states of samadhi for some time -- long or short -- the yogi gradually comes to distinguish between Purusha and satva. Satva is the most enjoyable facet of the mind and of creation, and the thing that all embodied beings most seek after. All people experience their satvic mind in the better dream states, in reveries and daydreams, in moments of epiphany with nature or or even blissful moments in the city, the recognition of a long-long friend, etc. The experience of the satva in the mind, which is God's higher nature, is enjoyed by the Practitioner and the Kshatriya for a long time. For some time he enjoys satva too much to be able to make this distinction, because the bliss of higher satva -- experienced in samadhi -- is all consuming and gives a divine drunkenness. But the highest attainment -- and the entry into the non-dualistic state of the sage -- comes when he becomes able to perceive a distinction between the bliss of meditation (satva) and purusha alone. This according to the Yoga-Sutra. In the Yoga-Sutra purusha is the one original Person, or God from whom all little identities arise. In Yoga-Vasistha terms, purusha is the "pure consciousness." In the Upanishads purusha is called atman. But this last discrimination -- the distinction he makes between satva and purusha -- is the last judgment the aspirant will make. After that this sage in the state of non-duality ceases from using his judgment and ceases from discriminating between one thing and another. He is established in Pure Consciousness or Brahman alone with no sense of identity. In this state he can only see Brahman, Brahman is the only reality, and all external things are non-different from Brahman. The Yoga-Sutra calls this highest attainment of yoga kaivalya, which means "isolation." And yet, from our point of view the sage is not isolated because his self is merged with all that exists and he knows all other peoples and things more intimately than we can comprehend. But this ultimate state -- the state of non-discrimination and non-judging -- is one that appears very strange to even most yoga aspirants. The state actually seems inhuman and unattractive to most. Yet, when in the presence of such a sage the sage is found to be powerfully attractive, because he is divine. The sage established in the state of duality has extreme renunciation and pronounced detachment from the world. In Indian terms a sage of such pronounced renunciation is called an avadhut or avadhuta. The Five Stages in the Bible Like the Bhagavad-Gita and the Upanishads, the Bible contains teachings that speak to different levels of religious realization, and Christ spoke teachings for the Adherent, the Seeker, the Practitioner-Devotee, the Kshatriya, and the Sage. Some of Christ's references to the sage established in non-duality are his teaching to "turn the other cheek," if slapped in the face; or to "sell all you have and give it to the poor and follow me" (wandering homeless), and "If a man forces you to walk a mile carrying his things, walk a second mile for him." Another is "When you give, don't let your right hand know what your left is doing." This means to give with complete detachment, without any prudent scheming and thinking, or even rational analysis. These teachings are ones of extreme renunciation and detachment, and only truly truly fulfilled and regularly followed by the Sage in the state of non-duality with no personal identity. In other places Christ speaks to the Adherent: "What did your prophets say?"

And to the Seeker: "Seek, and ye shall find."

"If a man is not willing to leave mother, father, and brother he is not worthy of Me." And to the Practitioner-Devotee: "And

thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy

soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this [is] the

first commandment."

"For there are some eunuchs, which were so born from [their] mother's womb: and there are some eunuchs, which were made eunuchs of men: and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake. He that is able to receive [it], let him receive [it]." And He speaks to the Kshatriya, who has been mastering all of the forgoing, when he tells them to go out into the world and "preach," or to bring the knowledge to others. All Gita quotations taken from "The Bhagavad Gita" translated by Swami Sivavanda, Divine Life Society celibacy.info |

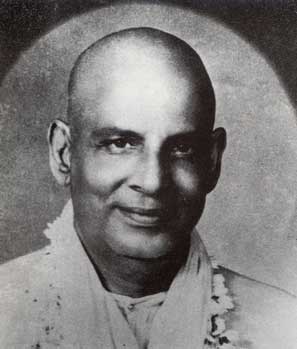

| Sivananda also was an adherent, then a seeker, then a practitioner, then a Kshatriya (defender of dharma and teacher of yoga and uplifter of the people), and also a great guru. |